Jellyfish are an important part of the Bay ecosystem.

Of the countless things you may love about the Chesapeake Bay, chances are pretty good that jellyfish aren't among them. Believe it or not, they are actually an important part of the Bay ecosystem. Here's a crash course on what makes these spineless creatures at least tolerable, if not somewhat interesting.

If you like oysters, you'll love jellyfish! No, not with lemon and cocktail sauce, but jellyfish actually eat predators that eat oyster larvae. So, in theory, more jellyfish means more oysters. Since oysters filter and clean our Bay water, jellyfish are like the sentinels that keep our oysters working hard at cleaning the water. Go jellyfish!

What are jellyfish?

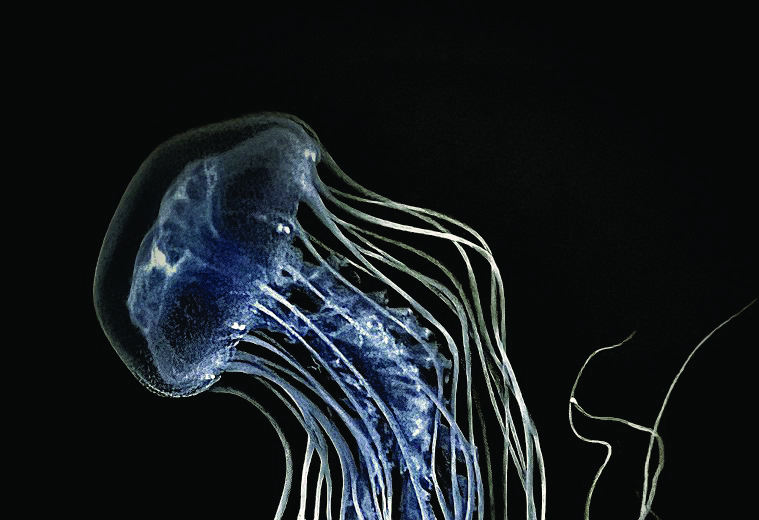

There are several types of jellyfish, but bay nettles are the most common in the Chesapeake Bay (Chrysaora chesapeakei). These spineless, gelatinous creatures pulse through the water, using their stinging tentacles to stun their prey for consumption.

Where are jellyfish?

NOAA publishes a report called “The Sea Nettles Probability of Encounters,” which maps the most likely areas of the Bay to find jellyfish. Currently those areas include the Middle Bay from the Chester River to Smith Island and the major tributaries in that range. According to NOAA, jellyfish are most likely found when the water temperature is between 79 and 86 degrees Fahrenheit and the salinity is 10-16 PSU. Areas with more fresh water and less salt water tend to have lower jellyfish concentrations, particularly after a period of heavy rainfall.

When do jellyfish come?

Jellyfish are always in the Bay, year-round, unlike our osprey, cownose rays, and countless other migratory species. We tend to see them more in warmer months such as July and August, because they spawn in mid-late summer.

Why they sting.

Like most dangerous creatures, jellyfish sting as a way to capture food. While jellyfish don’t eat people, their sting can be felt just the same.

Preventing a sting.

If you want to be in or near the jellyfish-infested waters of mid-late summer, covering up with a wetsuit or even pantyhose, can help provide protection from a sting. Just remember, a jellyfish could end up on your face, which would be rather unpleasant.

Treating a sting.

If you do get stung by a jellyfish, you should find the pain to be relatively mild. My most recent sting felt as if I had been scratched by a kitten. Common methods to relieve the sting include baking soda, meat tenderizer, vinegar, alcohol (hand sanitizer), hydrocortisone, and yes, it’s true—even urine.

Effect on boating.

Jellyfish can actually clog a boat’s sea strainer for the AC or engine freshwater intake, so it’s a good idea to check your strainers regularly during heavy jellyfish infestation periods.

What eats them?

Believe it or not, some fish and turtle species eat jellyfish, making them an even more important part of our Bay’s ecosystem. In several Southeast Asian countries some jellyfish species are considered a delicacy, with global harvesting estimated to exceed 300,000 metric tons. Personally, I prefer Smucker’s in a jar, but that’s just one man’s individual preference.

Like it or not, jellyfish are here to stay. Hopefully these fun facts might help them gain some appreciation among us two-legged creatures who share their home on Chesapeake Bay.

by Capt. Steven Toole