An Annapolis Sailing Couple’s Strategy and Daunting Journey Sailing Through Orca Alley

One hundred nautical miles southwest of Portugal, in the darkness of night, in the deep, open ocean, there was a long sigh of relief from the cockpit. You might expect nervousness or apprehension as darkness fell for the first time on a long offshore passage, but for us, we were happy and calm, for the first time in weeks. We had finally cleared Orca Alley on the way to Madeira.

As Annapolitans, we often cruise up Ego Alley, where perhaps the biggest danger is hitting another boat in front of hundreds of tourists. In Orca Alley on the west coast of the Iberian Peninsula, a whole new level of danger lurks. An unexpected attack from the famed Iberian orcas could result in a broken rudder, or worse, a quick trip to the bottom of the sea.

Starting around 2020, a small group of orcas began to interact with sailboats cruising along the west coasts of France, Spain, and Portugal and in the Strait of Gibraltar, bumping the boats’ rudders and toying with them, sometimes ripping them off completely. This behavior spread across a portion of the 45 members of the Iberian Orca pod and has now become more frequent.

During the first two weeks of October 2025 there were eight attacks concentrated in a small area just off the coast of northwest Spain in the province of Galicia. The day we left from Muxia, Spain, a boat that headed out at the same time came under attack two miles astern of us. We heard the call on the VHF letting the coast station know of the incident, and luckily there was no serious damage to the vessel. The reality of an orca attack became even more real and stayed that way until the day we left when there were another three attacks near our course leaving Lisbon.

To a sailor, it feels like a potentially life-threatening “attack,” but to scientists who study orcas, the behavior may just be juvenile orcas either playing with boats or simulating hunting for their preferred prey, the Atlantic bluefin tuna. These orcas are also known to feed on octopus that can be found near harbor entrances. However you characterize it, when an eight- to 11-ton, 20- to 30-foot-long, highly intelligent creature is determined to rip your rudder off and potentially sink your boat, it certainly seems like an attack.

We first heard of the orca attacks long before we contemplated buying a new Hallberg Rassy 400 sailboat in Sweden. It was an interesting news story, but it had little relevance to us. That soon changed as we placed an order for the boat and started planning our maiden voyage on Vellamo. We took delivery in May 2025 in Ellos, Sweden, and enjoyed a glorious summer in the Nordic countries, where the sailing season is short yet offers some of the best cruising grounds in Europe. We sailed blissfully through vast archipelagos off Finland and Sweden, beautiful towns of the Norwegian Riviera, and the deep fjords of western Norway.

As the days rapidly shortened, we crossed the North Sea to the Shetland Islands, down to the Caledonian Canal through Scotland and into the Hebrides. These areas are also known for orcas, the kind you hope to encounter at sea: beautiful and majestic creatures with no interest in your boat.

We continued south as quickly possible; the increasingly challenging weather chased us, finally making it to Northern France and the potentially treacherous Bay of Biscay crossing. The weather is the main challenge there, with frequent gales blowing in from the north, but crossing the Bay of Biscay was fairly easy, as we had time to wait for a perfect weather window. Then, the moment had arrived: we entered orca territory, where the fabled sea monsters of ancient times were still active and presented a real danger.

In Orca Alley our sailing skills would be tested in new ways. Planning, preparation, adaptability, constant research, and making connections with other sailors are keys to reducing risk at sea. For us, they were also the keys to reducing the risk of an orca attack. Here are a few of our tips and resources:

Keep track of the most recent sightings and interactions

There are numerous groups providing reports of orca sightings and hotspots and advice on what to do in the event of an attack. Our favorite was community-run orcas.pt and its associated Telegram group, which seemed to be fairly up to date and comprehensive. There are numerous other Facebook groups, apps, and government reporting sites, but orcas.pt seemed to be the best for us. Apparently, the founder, Rui Alvez, scours some 50 sources of information on a daily or more frequent basis and provides solid advice for avoiding orca areas.

Another good source for information and detailed reports of encounters is the Cruising Association, which has a comprehensive website: theca.org.uk/orcas. Finally, the Grupo de Trabajo Orca Atlántica-GTOA has a very good website and app: orcaiberica.org.

To say the information is scattered is an understatement. There are three countries potentially involved, France, Spain, and Portugal, and the coast from the Bay of Biscay to Gibraltar is 1500 miles long and not very populated. The attacks or encounters are largely at sea within 20 miles of the coast and experienced by sailors who are in the area for a limited period of time, transiting south to the Caribbean or hopping along the coast from port to port, as we were.

Keep track of fishing boats that might be fishing for tuna

The primary food source for Iberian orcas is Atlantic bluefin tuna which migrate from south to north over the course of the summer and fall and then back in the spring. These large tuna (up to 2000 pounds), look not unlike a modern spade rudder! Tracking an orca is apparently very difficult, but tracking a school of tuna is not. Commercial fishing boats do it all the time.

We used the Marine Traffic app to see where fishing boats were in general. We also used a free map from Global Fishing Watch (globalfishingwatch.org) that allows more detailed searches for boats fishing with specific methods, such as long line fishing commonly used for tuna.

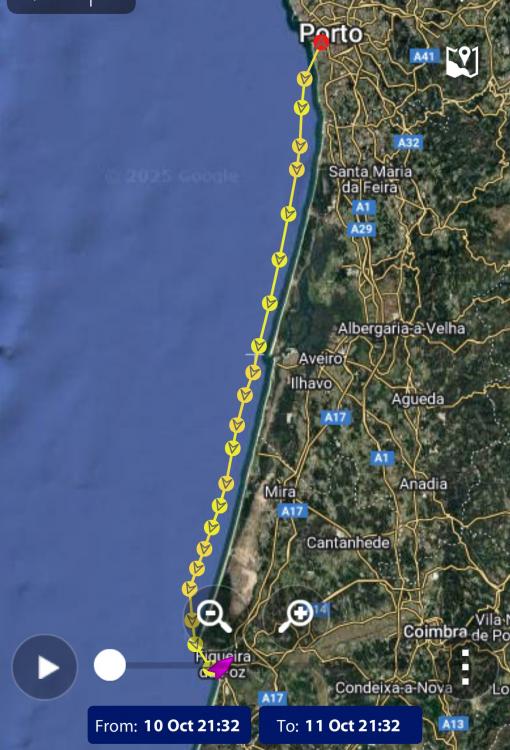

Stay in shallow water and avoid areas of recent attacks

The Iberian orcas spend most of their time following tuna, and tuna do not like water that is less than about 20 meters deep (65 feet). Very few interactions with Iberian orcas have taken place in shallower waters. So, in planning our course for the day, we tried to stay in 60 feet of water, which is only a quarter of a mile offshore in many places, so close that we were easily able to see people on the numerous beaches that dot the otherwise rugged coastline. As a result, we sailed less and motored more, but that was a sacrifice we were happy to make.

Staying close to the coast isn’t risk-free. A few weeks before we stopped in Cascais, Portugal, a charter sailboat had been attacked and had sunk in minutes by orcas in sight of the marina. The incident was caught on video from another boat. In that case, the orcas may have been hunting octopus.

Travel during the day when possible.

An orca attack during the day sounds bad enough, but one at night would be truly awful. Darkness makes rescue even more difficult in the event the boat is sinking. Shortly after we left Galicia in northern Spain, there was an orca attack on a sailing yacht at night at sea. A family with two small children was rescued in the darkness, and their boat was damaged and towed back to shore.

Have a clear plan of action in case of an encounter and wear lifejackets and safety gear at all times

We developed a clear plan of action and assigned roles to each other in case of an attack so that we could act quickly. The advice for dealing with an attack is constantly evolving, but our plan was to: 1) immediately disable the autopilot; 2) start the engine and go full throttle (in reverse in circles if possible); 3) furl sails; 4) empty holding tanks; and 5) deploy sand and any other countermeasures. We wore lifejackets and shoes at all times. If an orca attack were to begin, there would not be enough time to find and don a lifejacket.

Be prepared with deterrence countermeasures

Iberian orcas are a critically endangered population, so any measures that would harm the animals are illegal. Things such as making a piercing noise (fish pingers), using explosives, or hitting the orcas intentionally are a no go. Instead, we decided a strategy would be to make the water around our boat as unpleasant as possible by emptying our holding tanks, dumping sand around the stern, and making banging noises on our swim ladder.

The attacks have been known to last as little as a few minutes to as long as a couple of hours. Everyone has an idea about the best way to stop an orca attack, but in reality, there is no known effective deterrent once they have found you. The most effective thing is not to encounter them at all. Our countermeasures were probably more of a psychological salve for us than something that would have actually worked!

Luckily, we made it through Orca Alley unscathed and continued our trip south to Maderia. We are now in the Canary Islands, preparing to make the Atlantic crossing to the Caribbean, and ready to face the usual challenges of wind and sea. We are a little skittish still, looking over our shoulders as we sail, hearts pounding when we see a dorsal fin. So far, those fins have only belonged to playful dolphins with no interest in our rudders.

By Anne Nisenson and Peter Saari

Find more cruising stories.