A New Year’s Eve Night Sail on a 1949 Folkboat

The first night sail on Diana made for a memorable end to 1973 for Jeff Halpern, who now sails solo (and well) on the Chesapeake.

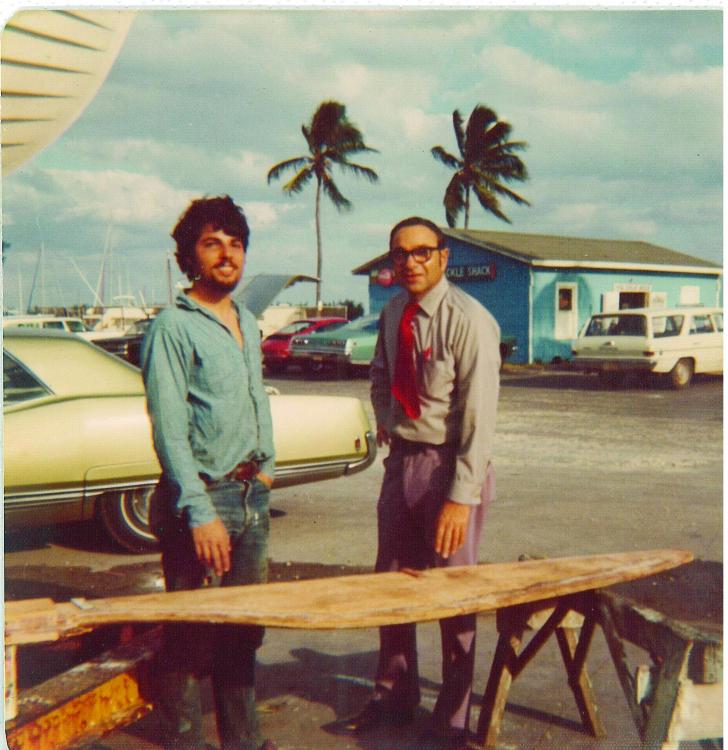

After graduating from college, I decided to save money, buy a boat, and live aboard while I decided what I wanted to do with the rest of my life. I landed a couple of minimum wage jobs, during the day working for a trailerable boat dealer that with no sense of irony called themselves Expressway Yachts, and parking cars at night. My weekdays were full of commissioning chopped glass wonders while my nights and weekends consisted of sprinting across hot Miami parking lots.

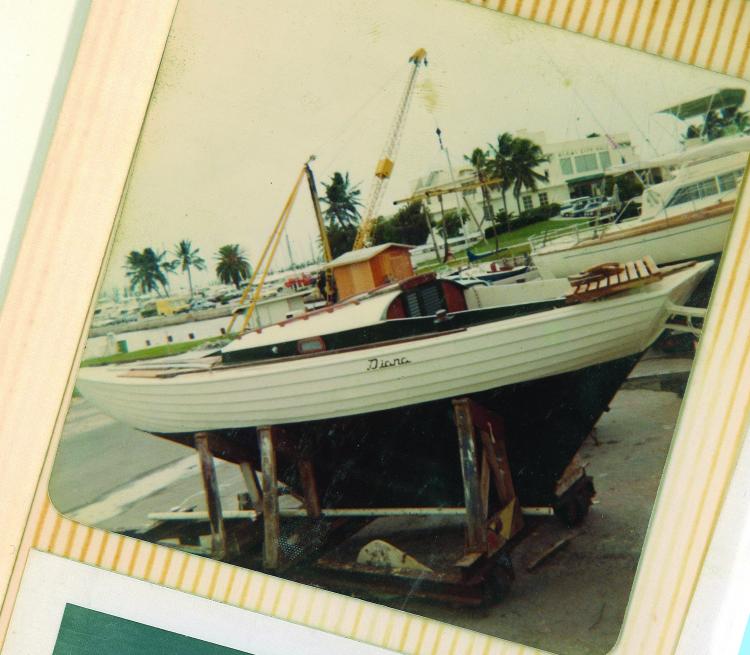

After a few months, I had put away enough to buy Diana, a near derelict 1949 Folkboat. I spent the next seven months replacing the rig, rudder, and keel bolts; sistering the frames; replacing floor timbers and planking; constructing a new cockpit and interior; replacing a piece of the stem and forward face of the cabin; and wooding and painting the bottom, topsides, and interior.

My yard bill was paid up through December 31, so I needed to get the old girl launched in time for the New Year. The yard closed down on Christmas Eve and would not open again until January 2. So it was that Diana was splashed around noon on Christmas Eve. Typical of launching a wooden boat that had spent so much time out of the water, as she was lowered on the marine elevator, she filled with water as fast as she was lowered to above her bootstripe.

Four hours later, with the flooding at a manageable rate, I bailed her out and floated her off her cradle. Even though the seams had mostly swelled closed, the theory with a wooden boat that has been out of the water for a period of time is that the planking must continue to swell for another week before you can stress the hull by going sailing. The yard let me tie up in the launch way for Christmas week but required her to be removed before the yard reopened.

That week, I slept on a slatted grate that I had made as a temporary cabin sole, my foot hanging into the bilge so that the rising water would wake me and let me know that it was time again to bail. After a fast week, it was suddenly New Year’s Eve. Diana needed to be moved. I had permission to tie up between an old piling and a bulkhead at the edge of the yard. I figured as long she needed to be moved, I might as well go out for a first sail.

This was to be my first sail on the Folkboat, and my first sail as the skipper of my own keel boat, one of the first times that I had singlehanded a boat this big, and one of the first times I had singlehanded at night. I pushed off just as the sun was setting into a classic sky-on-fire Florida sunset, beating east toward the narrow pass at the southern end of Key Biscayne in a light ghosting breeze neath the Jack-o-lantern sky, with a blood-red rising moon on the ever-darkening horizon.

A Folkboat is a marvelous little boat that can sail herself seemingly for days at a time. Inexplicably, I sat up on the cabin top, steering with the jib sheet in hand; bearing off by tightening and heading up with an ease of the sheet.

Diana was devoid of anything modern. She did not have an engine, an electrical system, or running lights. Being a few inches less than 25 feet on deck, I simply carried the required flashlight to shine on the sails. She had no lifelines or stanchions. Navigation was piloting with a folded chart and a tiny compass that was more at home on a car dashboard than the cockpit of a boat. She had no radio, and GPS was decades from being invented.

If you have spent time singlehanding after dark, you know those emotions borne of being alone at night at sea; the profound sense of being more alone than you have ever been in your life, the sense of tranquility, of speed beyond that felt in the light of day, of self-reliance, of fear that it is only you who can make the right or wrong decision out there, and only you who pays the consequences if the call proves wrong. The overhead carpet of unimaginably distant stars made me feel even more infinitesimally small and insignificant.

After hours in the chill breezes, I reached the mouth of the narrow, unmarked, coral-bordered channel into the Atlantic. Resisting temptation, I turned back for home on a broad reach in a building breeze. The trip back into the lights of Dinner Key is lost to memory, but when I arrived at the harbor, it suddenly occurred to me that I had never brought a boat this big into a dock alone under sail. I sailed back out into the mooring area and practiced a couple of approaches to the piling.

Youth is an amazing thing that brings a confidence that can only be had when you don’t know the consequences of making a really big mistake. Seen through the rose-colored optimism of youth, it made complete sense to me to steer into the dock controlling the direction of the boat with the jibsheet while sitting on the foredeck. I figured that if I missed the piling, I would fetch up on the sand bar just ahead of the piling.

In youthful confidence I came roaring in on a beam reach, sitting on the foredeck, jib sheet in hand. At the moment of truth, I freed the jib sheet and Diana pirouetted gracefully up into the wind. I grabbed the clew of the jib, moving it from side to side, steering and slowing the boat, and coming to a dead stop right next to the piling. Polite as you may, I threw a bight of a dockline over the piling.

There I stood, dockline in hand, congratulating myself on a job well done, cold and numb, a toothy grin across my face, scanning the docks for some witness to my brilliant feat of seamanship. No good deed of seamanship goes unpunished, and in my moment of self-congratulatory elation, nature took its turn by hitting Diana with a gust from the opposite side of the jib from where I stood perched on the narrow foredeck, and shoved me hard towards the rail. As I went over the side, I dove for the shrouds, grabbing the lower shroud with my forearm, slicing it deeply on the Nicropress fitting that should have been taped for just such an occasion, and dropped feet first into the cool December waters of Biscayne Bay, but still keeping my grip on the boat.

As I hung over the side, legs in the water, I tried to decide whether to let go and fall backwards into the water, or pull myself aboard. Remembering a paycheck in my wallet, I pulled myself over the rail and back aboard.

My scream as I went over the side had drawn a crowd from the boats tied up nearby, who arrived just as I pulled myself back aboard. As I lay there on the foredeck, winded and bleeding, soaked and shivering, the sound of fireworks and firecrackers bursting in the distant darkness and the chorus of Auld Lang Sine from the drunks in the local juke joint wafted out to tell me that I had just entered into the brand New Year of 1974.

~By Jeff Halpern

Find more cruising articles here.