It didn’t take long after arrival at our marina about 45 minutes’ drive away from Split, Croatia, to conclude that things were different there. My husband Rick and I, along with our friends Skip and Harriet, had arrived from London around 2 p.m.; Pat and Emily had already spent a few days in Croatia and were relaxing with the local Karlovačko beer. The Sunsail marina was a mob scene, as taxi after taxi unloaded arriving sailors. I lined up at reception to check us in. It turns out that most sailing charter vacations in this region start on Saturday afternoon, so we were jockeying for resources—space, attention, provisions—with every other crew sailing in Croatia this week.

We found our local skipper, Roko, and were off the dock by 4 p.m. The fact that we had a skipper enabled us to skip boat and chart briefings. We’d provisioned some essentials with Sunsail which were already stowed for us, so we beat the rush. This turned out to be no insignificant thing. The fact that I knew hardly anyone who’d ever been to Croatia did not mean that this was some secluded, undiscovered destination. Europeans know all about the Dalmatian coast—it is beautiful and historical, convenient to reach, still relatively pristine, and affordable—and they flock here in droves. Roko’s first choice for the night’s destination was already full, so we went to his second choice, Šešula bay off the island of Šolta.

Šešula had no marina and a bottom so hard that anchoring was out of the question. Instead, in exchange for use of a mooring, we agreed to dine at the associated local restaurant.

Mooring is the way to go here, often with a line attached to the sea bottom, and another attached to the shore. But you are not alone on the mooring. By the time we sat down for dinner, we were wedged among more than a dozen boats, separated from our neighbors only by a fender’s width. Although we were initially skeptical of the requirement that we sail with a local skipper (since we didn’t want to bother with obtaining the required license), the mooring situation would have been bewildering without his expertise.

Night after night, we wedged our 26-foot wide catamaran stern-to into a marina, or stern-to at a village quay. Except for that first night, every place we tied up offered, for a modest price, electricity and un-metered water (this is a luxury especially appreciated by me, who could make 100 gallons of fresh water last over three weeks in the Bahamas, and still treats water as a precious commodity).

Each evening was more crowded than the last, and it helped immensely to have the local knowledge that Roko offered; with a phone call he could suss out where there would be room for us, while other sailors not so fortunate begged for spots at the dock, or spent miserable nights in less than ideal spots, rocking and rolling in the swell. Roko also knew where the infamous Yacht Week flotilla was headed day after day so that we could (mostly) avoid them.

I had no objection to the partying that was associated with the Yacht Week flotilla (only jealousy for the fact that such a thing didn’t exist, and I could not have afforded it when I was a 20-something!), but there were so many of them that lines for marina showers and toilets were inevitable. But we soon became accustomed to the crowds of boaters, and our proximity to them; instead of defaulting to our North American tendency to try to make friends, we learned to ignore them.

Though we thought a local skipper would have been useful for his language skills, it turned out that just about everyone we dealt with spoke English. Those who didn’t were friendly enough that we could make ourselves understood. Roko’s greatest accomplishment was arranging culinary experiences. While waterfront dining catered more to tourists—though one can hardly complain about fresh caught seafood—Roko got us off the beaten path.

Twice, we took taxis up the winding roads up into the hills of the tiny islands we visited and ate at remote establishments that offered the best of the islands. On terraced hillsides, under the shade of an ancient spreading tree or rough-hewn timbers, we dined on spit-roasted lamb or hearth-grilled octopus, accompanied by house-made cheeses and locally grown vegetables, and carafes of delicious local wines.

I wasn’t quite sure what to expect of food and provisioning in Croatia, but what I found was an entirely Mediterranean experience. Having provisioned only beverages and some basics, we found in every village one or more small food stores or markets. We went out to dinner almost every night, while composing lunches of fresh-baked bread, beautifully ripe tomatoes, local ham much like prosciutto, stinky cheeses, and briny olives, most of which we picked up along the way. Fresh croissants and donuts also found their way aboard in the morning. And everywhere we could find a potent espresso. We were, of course, just across the Adriatic Sea from Italy, and up the coast from Venice, so the similarity to Italian cuisine was not accidental.

Although we were on a sailboat, there was not much sailing to be had. A one-week itinerary is necessarily limited, and we didn’t have enough time to await optimal wind and sea conditions to reach the islands of Šolta, Brač, and Hvar. Aside from lack of wind, the June weather was sublime, with bright sunny days in the 70s, and cool nights. Alas, the crystalline green waters were prettier to look at than comfortable to swim in: the water was freezing! And “beaches” aren’t much to speak of, as the rocky mountains of the islands fall precipitously into the sea, with few flat spots to make a gradual entry.

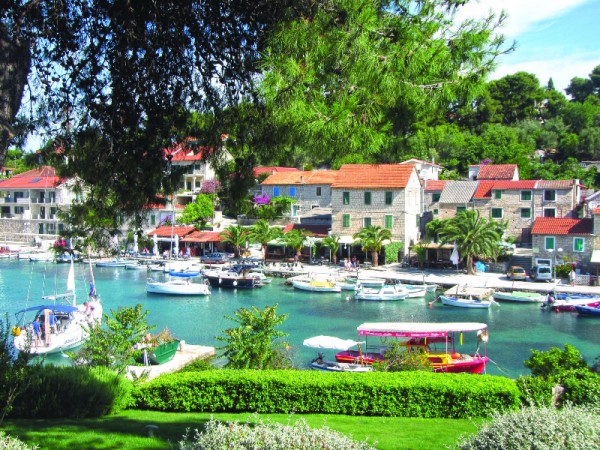

And so we were forced to spend much of our time wandering the narrow streets of impossibly pretty villages built of indigenous stone, some of them more than two millennia old, spending our Kuna (local currency) on lavender harvested from the hills and soap wrought from olive oil. After climbing uphill, we’d gaze down on blue harbors surrounded by palm-lined quays, rewarding ourselves afterwards with purchases of wine poured from casks into water bottles. For this, we hardly needed local assistance, for I’m convinced that any hamlet we might have stumbled upon would have been picture-perfect.

~Eva Hill

This article first appeared in September 2015 SpinSheet