Sailing to Haiti: first light and busy with my departure

The anchorage had been a good stop on my sailing trip to Haiti. I was in south Man Of War Bay on the west side of Great Inagua Island in the Bahamas, where Ave Del Mar and her buddy boat, Still Free, a Compass 30, had enjoyed protection from those trade winds that whistle in from the east. Their captains had enjoyed a good night’s sleep while en route.

First light found me busied with my departure, with oatmeal and coffee and the straightening and stowing that has to happen for a comfortable day. The last of the morning dishes were done and stowed, and the tanbark main was high on the mast as the anchor came up, hand over hand, pulling out of the soft sand with a silent sigh that I could feel through the chain. I was underway again and underway is always good, but it comes to me hand-in-hand with a nervous anticipation that hangs in the air like a sniff of lavender on a morning walk. Every departure should be this way, I reminded myself. Complacency gets no berth on my boat. Nerves mean I am alive, thinking. On task.

I had to make about four miles of west-southwest progress to reach my mark at 73°44’ where I would bear south and sail off for the great unknown of western Hispaniola. Ave was unhappy with our start as we rolled through an awkward swell under a quiet morning breeze that found itself dead on her stern. Every passing wave swung us like a metronome. The genoa filled with a snap one minute only to fall limp or attempt an unassisted gybe the next, so I made my way forward and wrestled the whisker pole into place, none happier with the boat’s motion but much relieved at the taming of the sail. I leaned back against the high combing of the cockpit and braced myself first this way and then that as Man Of War Bay fell all too slowly away.

We were passagemaking

The morning winds gradually built, but I was resigned to the likelihood of another slow, clumsy sail as the early morning crept along. When we finally hit our waypoint I pushed the tiller to starboard. Suddenly Ave sprang to life like a startled thoroughbred, picking up speed and sending the leeward toe rail down for a saltwater rinse. The whisker pole returned to its lashings on the deck with the swell comfortably on our port quarter, and life turned on a dime. We were sailing. We were passagemaking. We were headed for Haiti at breakneck speed.

Glory sailed with me that day as mile after mile of southward progress sliced effortlessly past the hull. Behind me, my Uruguayan friend Aldo on Still Free fell steadily away until he was out of sight, a strange turn from those light-wind days when he raced ahead of my slow, full-keeled old boat. Hour after hour the trades did what they do, bringing a steady 20 knots out of the east-northeast, and Ave continued to express her happiness with the state of our affairs through toe rail rinsings, taut sails, and an unwavering course.

Nightfall found me doing what I do on a good passage: catnapping on the port cockpit bench, properly clipped in on the captain’s side. A raise of my head for a scan of lights on the horizon, a touch of the jib sheet every now and again to sense the load, or a glance at the AIS gave purpose to waking up, but the only excitement that found me was the thrill of unabated progress.

Landfall in the dark of night

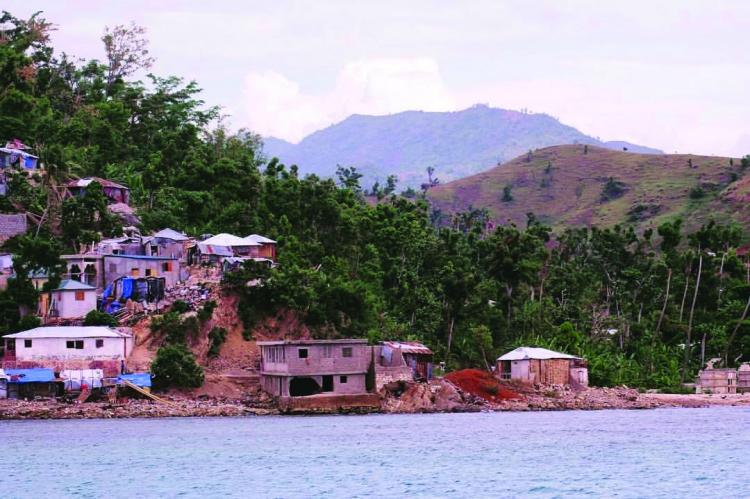

I could smell Haiti before I could see Haiti, as the campfire-scent of its ubiquitous cooking and trash fires wafted north through the night sky. Sleep became fleeting as anticipation took root. My passage had been too fast, too efficient, and my landfall at Môle Saint-Nicolas on this small Caribbean country’s northern peninsula would have to happen in the dark of night. In the words of Kurt Vonnegut, So it goes.

The approach into the bay was straightforward on paper, with deep water and no charted coral heads or rocks, but open-ocean sailing plays with your perspective and all I could see of the real Haiti ahead of me was an imposing mountainous silhouette, jagged and threatening, inky black against the starlit sky. I reduced sail. Ave slowed, her bowsprit pointing into the dark like a lance in battle. Sail 20 hours, and then aim for the cliff seemed a questionable strategy, but I crept on. Time disappeared. My confidence faded with it like a last gasp of light from an oil lamp.

I turned the radar on and stared—first at its glowing green image and at the plotter, back and forth, head on full swivel as a man at a tennis match. The shoreline drew closer, closer, and then closer yet. Slowly I sailed on, ears on alert for the crunch of my boat bashing into rocks. Pick a point to turn. Wait for the crunch. Can’t turn yet. Sail. Steer. Wait. Listen. This cannot be right played in my head like an endless electronic loop. When that moment finally came, and I jammed the tiller hard to starboard and swung east into the bay, my hand was wet with sweat. The mountainous shoreline, dark and threatening, was a scant half mile off my bow.

In the night lee of that staggering skyline I doused sail and motored in to anchor in the far end of the bay. Hours later, Aldo’s arrival on Still Free came accompanied by an urgent, “John! John!” in his heavily accented English over the VHF.

“I do not like this,” he said to me from his handheld.

“Aim for the cliff, Aldo. There’s room.”

“I do not like this,” he replied, but ventually he made the turn, sans crunch, and motored east, his light boat tossing back and forth in the swell.

“Very rolly!” he barked over the radio. “I can’t see you. I do not like this.”

“I’m anchored, Aldo,” I said. “Keep coming. You’ll see my anchor light.”

And he did, coming to rest in a beautiful patch of 12-foot deep water I had left free just for him. I watched him from Ave’s cockpit, brightly lit by his spreader lights, as he clamored to his boat’s foredeck in his underwear, as always, all skin and bones and that proud Uruguayan mustache. The anchor spilled over the bow and Still Free fell to rest without fanfare.

With his hands on his hips Aldo looked at me and slowly, ever so slowly, a mammoth smile spread across his weathered face. “Wow,” he said.

Wow, indeed! I thought, as I made my way below to the comfort of my bed. Welcome to Haiti.

by John Herlig