A Sailor Faces His Bridge Clearance Fears

The problems from the first few days of the delivery were common ones: charging issues, an oil leak, and a feathering prop that didn’t want to feather. But hitting the Morehead City Bridge in Beaufort, NC, was a new wrinkle.

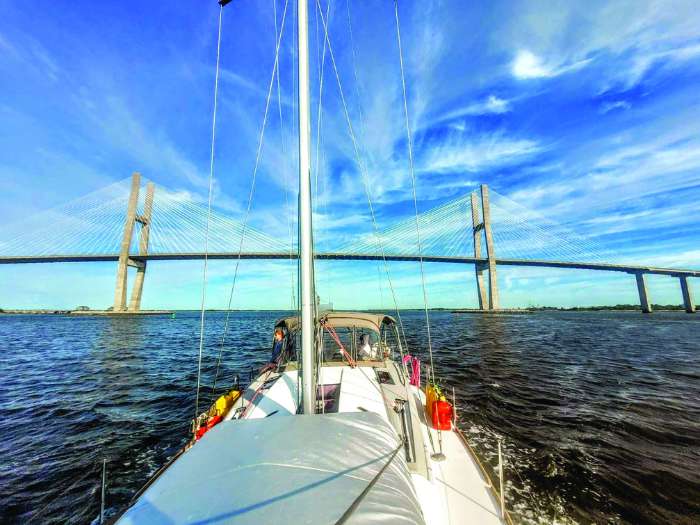

Despite the owner being onboard, responsibility fell on me, as I was the captain. As many times as I have tried, I can’t quite recreate the exact sequence of events that led to our mishap. We discussed our air draft before we departed Georgia and information about the 2013 Jeanneau Sun Odyssey was passed along from her new owner to me. Notes were made and plans were drawn. I knew we were a bit tall, but I also knew that we were ICW compliant… on paper.

Cape Hatteras and the Graveyard of the Atlantic loomed large ahead of us as we sailed north under worsening conditions, and soon enough, bailing out into Beaufort looked inevitable. It was at the entrance to the inlet that one of my crew pointed out that it was Memorial Day Weekend, which marks the official beginning of the summer boating and fishing season and the day all unqualified boat operators decide to operate boats. Most of these folks appeared to be in Beaufort.

The first order of business was to take on fuel and water, which we successfully did after waiting for about 100 center consoles to drift this way and that so that we could turn into the current and tie off to the fuel dock. With our tanks full, we pulled off the town dock and anchored in Beaufort’s narrow basin where the crew napped, cooked dinner, and eventually all went to bed at a shamefully reasonable hour. The next morning our delivery switched from Mother Ocean to the Intracoastal Waterway, bringing a relief that did not last long. In fact, it lasted only until the first bridge.

The details get a little murky as I try to recall approaching the Morehead City-Newport River Bridge, details that included how high I had been told the mast was, the unknown amounts of “stuff” atop the mast, and an impossible-to-read tide board that showed something around 65 feet. Or maybe it was 63. Parts of my brain thought it was enough. None of my gut agreed. We approached the bridge at a crawl.

My junior crew was on the foredeck watching the masthead through a pair of binoculars while my second in command was in the cockpit next to me. I handed her the air horn. “Just in case,” I said. We approached the bridge’s fenders at forward idle, making just enough speed to maintain steerage. As we reached the fenders, I slid the boat into neutral, knowing she would glide. By the time the top of the mast approached the first bridge girder, I had her in reverse idle. Just in case, I told myself.

The crunch of the windex hitting the girder wasn’t terrible, all in all. The junior crew let out a shout to reverse course. I looked at my number two with the air horn. “Five blasts,” I said. “Now.” My right foot kicked the throttle astern. The prop bit, and the boat began extricating herself from the bridge as the airhorn wailed its warning. Looking up I could see that we still had a VHF whip, and we still had a mast. It could have been a lot worse. We limped a short distance out of the channel, dropped the hook on a short stretch of chain, and took stock of the boat, what we had done wrong, and what our options were.

We gleaned information from every possible source including a more accurate assessment of our air-draft from the owner’s manual, innumerable texts with friends who have similar clearance issues, and a more refined examination of the tide charts. The bottom line was simple: every option stunk. The high-masted folks are no doubt tsk-tsking me for being so naïve. I probably deserve that. I didn’t appreciate your challenges.

A couple of strangely relaxing hours at anchor by the bridge were enough to let the tide drop, and when we reattempted the bridge’s spans, we sailed through without incident. The telltale ting! ting! ting! of the VHF whip snapping under the bridge girders was the only evidence of our height issues. We carried on northward.

The promise of clearance issues at the Hobucken and Wilkerson bridges had none of us very excited. After a full review of our choices, the owner and I decided to try a challenging shortcut called The Old House Channel. This route runs through the Pamlico Sound past Pea Island and east of Roanoke Island, far removed from the scariest of the low-clearance bridges of the northern ICW, but through a seemingly endless stretch of shoaling waters that are sometimes virtually impassable. We both preferred the thought of a soft grounding over a dismasting by bridge and so made the decision.

The timing left us transiting our shortcut in the dark of night, during which our junior crew picked out unlit day markers with the cordless spotlight while my second was just outside the cockpit reading water depth and communicating back and forth between me and the foredeck. We crept through the unforgiving channel, zigzagging around shallows, and shoaling in the darkest of dark. The owner sat at my elbow, watching the depth gauge with wide eyes.

Freedom was just around the corner as we approached the Washington Baum Bridge at sunrise. The bridge drill remained the same. We approached at forward idle, dropped her into neutral as we passed the fenders and into reverse idle as we neared the spans. The VHF whip didn’t go ting! ting! this time—it bent down almost horizontal. As we escaped the bridge’s spans, it sprung back, none the worse for wear, apparently. The gauntlet had been run, and we were still in the game.

With this challenge behind us the crew drifted belowdecks for sleep as an ecstatic owner and I shared the cockpit in the afterglow of a trying day. “John, that was amazing!” he said to me as we motored back toward the traditional ICW path. “I just don’t know if I should punch you or kiss you.”

About the Author: John Herlig is a delivery captain on the US East Coast and the Caribbean, a teacher at Cruisers University, and a boat driver for the Annapolis Boat Shows. Find him at [email protected].