A Bay sailor's military background parylays into sailing leadership skills

Ask anyone who’s done it, and they will tell you that preparing a boat and crew for sailing offshore is a big undertaking. It takes planning, organization, communication, and much more. Leadership training, attention to equipment, and precise communication are but a few of the many skills that we thought might be enhanced by military training and then parlayed into a successful offshore sailing campaign. So, recently Team SpinSheet checked in with one local Chesapeake Bay sailor, a Marine Corps veteran, and asked how his military background has helped him in preparing and executing his successful offshore racing campaign.

Lt. Col. (Ret.) Scott “Gus” Ward, a Bay sailor and former Marine Corps AV-8B Harrier pilot, has been racing sailboats for more than 45 years at a world, national championship, and professional level in dinghy, catamaran, and offshore racing events. Originally from California, Ward has been a Maryland resident for many years, is a member of Storm Trysail Club and the Southern Maryland Sailing Association, supports US Patriot Sailing, and is a coach with the U.S. Naval Academy’s Varsity Offshore Sailing Team (VOST).

Ward has been at the helm of his 50-foot Crocodile (previously he owned a smaller Beneteau of the same name), sailing out of Solomons, MD, since 2016. His crew is loaded with seasoned offshore racers, most of whom are Navy or Marine Corps veterans. They’ve competed in the Annapolis Bermuda Ocean Race (A2B), Newport Bermuda, and Annapolis to Newport, and other high-profile races. In 2018 Ward served as a watch captain and helmsman in the Sydney Hobart race. Closer to home, the Crocodile team can be found on the line for most of the big Chesapeake Bay distance races.

Sailing preparation: a “what if” mindset

Ward says that a Marine’s focus on equipment has served him well in preparing Crocodile for offshore racing.

“Marines take an intense fascination with their equipment, ingrained early on in both Boot Camp and Officers Candidate School by very zealous and talented drill instructors. There are good reasons for it: stuff has to work when needed in order to both execute the mission and keep fellow Marines and peers alive.

“Preparing a boat to race offshore is very similar. Systems and equipment have to work, both to protect the crew and run the boat as quickly as conditions permit. Confidence in a boat only comes with a continuous mindset of assessment; preparation for a Crocodile offshore race starts months prior and includes all aspects of the boat. From the keel and bolts, rudder, sail drive, and bottom condition, to running rigging, internal systems, electronics, and sails—everything gets looked at and addressed if needed.

“The mind set applies a “what if” process, so there are a lot of redundancies, which can pay dividends, as was the case in our 2018 Newport Bermuda Race. We took a 2 a.m. knockdown from a roll cloud and ended up with an ingress of water into the nav station and causing two subsequent electrical fires. Instantly we went from a cutting-edge electronics package to Kon Tiki—compass heading and steering to stars for a bit until the backup laptop and equipment could get unpacked and online. This was something we had planned for but hoped would never happen. Having the ability to quickly go to a working backup and resume navigation allowed us to focus on finding the source of the electrical fires and reset from survival mode back to racing.”

An annual Crocodile Safety Sail, which is mandatory for his major offshore racing crew, focuses on yearly boat system familiarization, safety gear training, sail handling mechanics, night sailing, initial watch section introduction, and cycling through the different positions: bow, pit, helm, nav, trim, and foredeck. Among the “what if” scenarios that the crew prepares for: MOB, fire, taking on sea water, steering issues, rig failure, and abandoning ship.

A place for everything and everything in its place

“It is always difficult in the middle of a 750-nautical mile race to keep organized as everything below looks like a tornado came through, but there must be a basic system so that onboard operations can happen in an orderly fashion,” says Ward. “The sails on the top of the pile ought to be matched with the forecasted conditions, and the gear needs to be out of the way for watch changeover. Obviously this applies for safety and ditch equipment too.

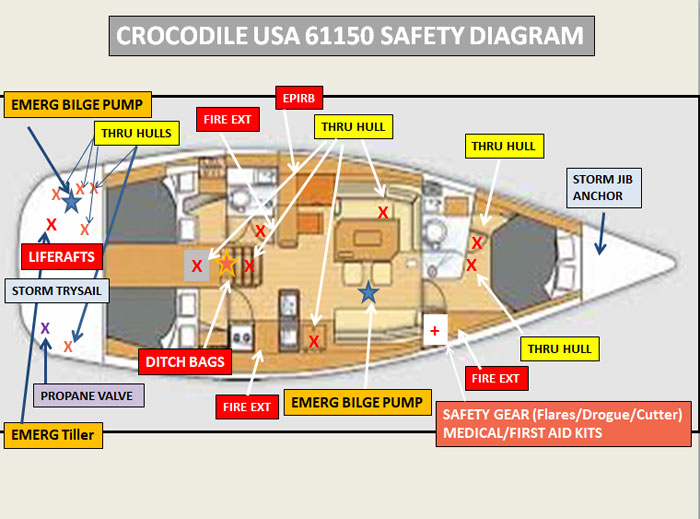

“The Crocodile Equipment Diagram is prominently displayed and shows where all safety equipment lies throughout the boat. The crew knows where everything is and what they are assigned to in case the abandon boat decision is made. All critical gear is labeled in accordance with the ISAF Offshore Regulations and also additional common sense items (what is really in those first aid kits, and how do you find bandages in a time-critical situation?).”

On sailing leadership and communication

If an offshore race or passage is the time for a skipper to tap into his full set of leadership skills, Ward says it’s the skipper’s job to lead with calm communication, while relying on the strengths of each crewmember.

“I strive to understand individual chemistry, apply and lean on each person’s strengths, respect the skill sets and experience I have been blessed to have gathered, make sound decisions, and then get out of the way, let the talent loose, and steer the boat like you stole her.

“Calm, rational communications mixed with humor are always important, with an emphasis on calm. Stuff tends to happen at night when everyone is fatigued, and you as the leader need to work through problems and challenges drawing on everyone’s strengths and skill sets at all times. Everyone, no matter the experience level, brings something to the table. You, as leader, are responsible to bring that out.”

Ward continues, “Did I mention calm, rational thoughts and sentences? I have the distinct pleasure to sail on Pursuit with Norm Dawley, who is the epitome of a proper skipper and great quiet communicator. I am proud to say that Dawley has taught me many communication techniques. He has the ability to extract maximum focus and effort from everyone, no matter the conditions, while always making it enjoyable. Temperature is 110 degrees and two knots of wind? Blowing 45 knots with cold green water? No problem. We (his crew) are all younger, but he always seems to be hotter, colder, and/or more wet. Despite this, he always exudes quiet humor and amazing knowledge. His demeanor always motivates; multiple sail changes at 2 a.m.? ‘No problem-let’s do it!’”

Coaching with the U.S. Naval Academy's Varsity Offshore Sailing Team

Bay sailors are fortunate to have one of the best sail training programs in the country at the U.S. Naval Academy (USNA), where Ward is a part of the coaching team.

Ward says, “I am honored to be a volunteer coach for Jahn Tihansky’s Navy VOST (Varsity Offshore Sailing Team) team and be a contributor to a process that takes Midshipmen who have never sailed on a boat to winning, experienced, offshore teams in an incredibly compressed timeframe. Starting in the winter of each season with classroom academics, during the spring, these outstanding future leaders are trained daily beginning with basic seamanship and safety maneuvers and building quickly into cohesive team units in weeks, ready to tackle initial events offshore and taking on tactical and strategic planning and execution. By early summer these teams, led by experienced teammates, are ready and competitive in the offshore arena. This last season is a great example, as the team enjoyed notable results in their events.

“On Crocodile and the Navy boats, we hold a pre-brief before each race/practice, much like I did when flying. As a tactical pilot, it is standard practice to spend up to seven hours preparing for the complexities of deep air strike, close air support missions, and then briefing the entire flight in a set format and time, to enable all participants a full understanding of the plan and contingencies for the mission/flight. This battle rhythm, whether combat or training, offshore/buoy race or practice, serves as a critical component to ensure the entire crew knows the conditions, plan, and ‘what ifs’ prior to leaving the dock. Post briefs are also standard in military flights and very effective with race teams. They enable crew mechanics to be fixed, equipment setup, and repair needs. USNA VOST adheres to these methods as a baseline method to maximizing each individual and crew learning curve.”

“I blend my Crocodile race schedule with VOST, which enables a unique opportunity to coach on the VOST boats and offer my military and sailing experiences. If the schedules line up, the Croc team also races against the same VOST teams (lots of good natured challenges when this happens!), and on occasion VOST sailors race onboard Croc if their leave schedules allow.” While Ward says he thoroughly enjoys passing on his military and sailing knowledge to the Midshipman, it can be a two way street. “I also learn from them, as they are always coming up with ingenious solutions to strategy, problems, or making the boat go faster.”

Team Spinsheet is happy and encouraged to hear about the innovation and energy of the next generation of sailors, and we thank Ward and all our active duty and veteran military sailors who share their skills on the Bay and beyond.

By Beth Crabtree