An Orca Encounter While Sailing Offshore

Severin Kodderitzsch, the square-jawed German owner, doesn’t swear much. So, when I heard the word “Scheisse!” hissed in the cockpit, I was shocked. I knew it was time to reach for my shoes. I jumped from my damp starboard bunk, my weather gear already on, for we were sailing offshore on the open Atlantic, in deep water somewhere off Portugal, in a 28-foot Albin Vega, headed for Lisbon.

Severin is a conservative sailor—he wants harnesses on at all times on deck, headlights mandatory at night. He was at the tiller at about 2:30 a.m., with the moon a yellow lantern, revealing black fins and bulky bodies splashing and blowing alongside with the telltale show of white. Their strange squeaks were audible. These were not porpoises but Orcas, and there were several of them, much too close. It was so calm. We were motoring with full genoa and main slack. Severin shouted, “They’re hitting the boat.” He jammed the little two-cylinder Beta diesel into reverse, “They’ve got the rudder. Get away!” he shouted into the night.

I could feel the boat swinging, much too quickly, too many degrees, and a sharp bump to the hull as if we’d hit a log. Meanwhile the tiller was torn out of his hands. When he grabbed it, it was lifeless, a hardwood handle attached to nothing. “No steerage,” Kodderitzsch said calmly. “We’ve got to do something to get help.” I reached for the tiller and got no return pressure—it moved far too easily. I couldn’t believe something so important was broken on such a calm night. Severin, however, more quick-witted, was already on channel 16 and voicing words I’d never heard in 65 years on the Atlantic.

“Mayday,” he said after hitting the button, “Mayday… This is sail yacht Barbarella. We have an Orca attack, and we can’t steer.”

It was an accident you couldn’t believe happening. The boat drifted, motor in neutral. Seas nearly calm, halyards tapping and the moon staring. A brief discussion, and I started foredeck duties, wrapping the genoa and getting the main quickly stowed on the boom. Severn dove to the floorboards “No water,” he shouted. “At least the hull is okay.” The Orcas, possibly four to five, were still visible. They disappeared as suddenly as they’d arrived. And now from being a trim cruising machine, we were as helpless as the old-time trading schooners and brigs.

Remarkably quickly a loud voice spoke from our electronics: “Your number, your position, your situation—are you taking water? Are their injuries?” So well was the little yacht organized that all the particulars were right there, the long and lat on the navigation screen, the yacht’s identification number and identity for the international identification system, all posted on a neat sign inside the companionway, and now in the possession of the Portuguese coastal authorities.

A port called Peniche

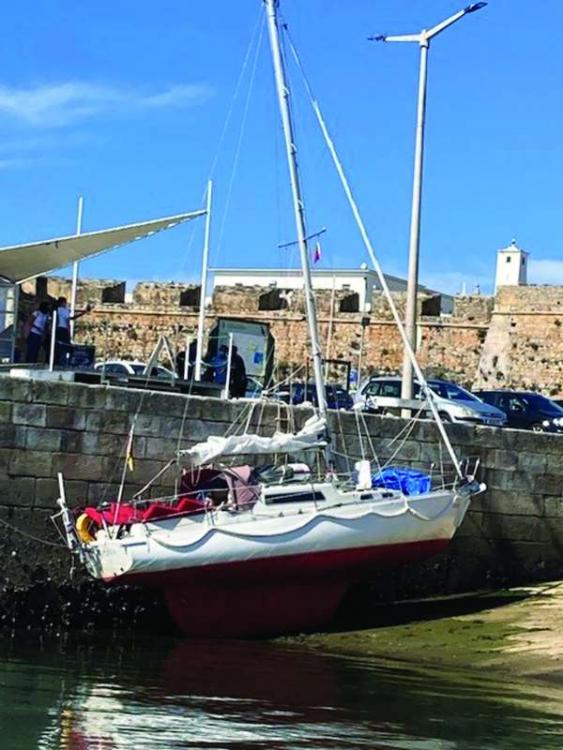

In less than an hour they arrived in a hard-bottom inflatable with two big outboard Yamahas and two men onboard. We were under tow after the shouting, heading for the old fishing port of Peniche, which we could soon smell on the cool night air. Staring with headlights at the rudder head, neither of us was willing to say it, but it looked like the end of our cruise.

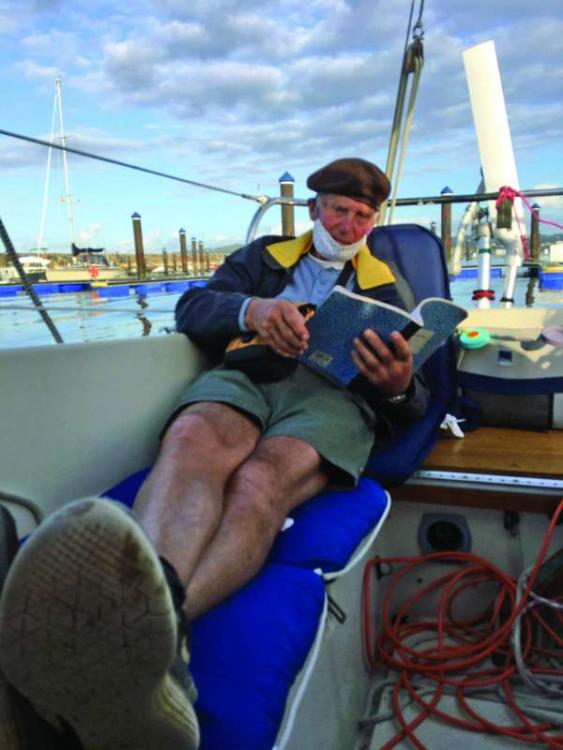

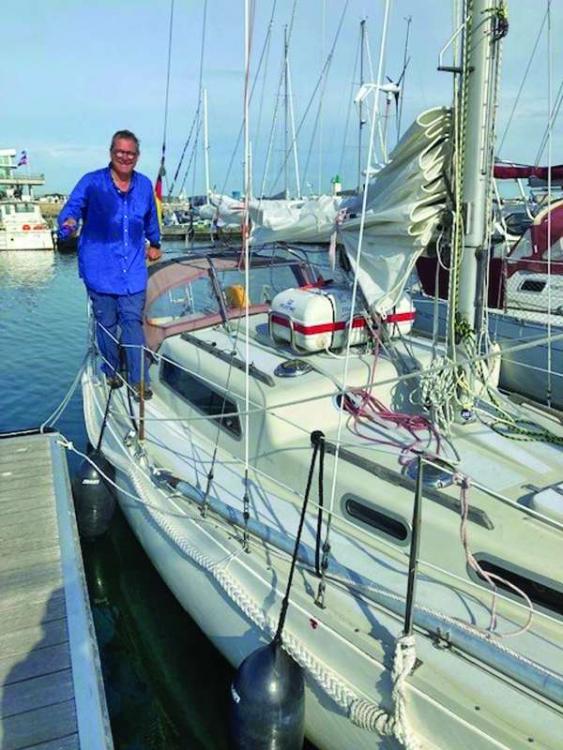

An experienced singlehander, Kodderitzsch had been cruising the coast of northern Europe for months, with Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, England, Spain, and France under his belt. His system was methodical: careful study in his well-thumbed copies of “Reed’s Nautical Almanac” and the “Admiralty Pilot” volumes covering the coasts, contacts with electronic aids such as the Passage Weather and Windy websites, and others. The yacht itself, though over 40 years old, was stout glass and epoxy layup—single layer in the old style, immaculately maintained and equipped, hoisting new Dacron sails from the Hamburg sailmaker Segel-Raab, a four-man liferaft in canister, and many other extras for ocean work.

He’d cruised from port to port, living the ideal sailing life he planned during a career with the World Bank. In several years residence in Washington, DC’s Capitol Hill, where I’d met him and sailed with him from Galesville to Florida, I knew him as a jovial, intelligent amateur who soaked up information and had embraced small-boat voyaging.

I’d joined him only for the truly ocean passage, the route across the Bay of Biscay from Brittany, France, to the tip of Spain and down the “Portuguese trade” northerlies to Lisbon. He wanted a full crew for 24-hour, four-hour watch operation in the Biscay, and I had done the passage several times. All had gone well—this September’s Biscay was mild with varied winds, not the reaching breezes the full-keel Albin Vega needs to achieve speeds over five knots. We had the predictable gale running down from La Corona, Spain, to Portugal under reefed main and 100-percent jib alone, only to run out of wind about 70 miles from Lisbon.

Orca attack or playful behavior?

On the rescue tow we schemed what to do. Peniche, the fishing port, is famous for its sardines, had a yard which could haul Barbarella and a yacht club which had a crane; these things we could discover quickly on the iPhone. Kodderitzsch had four languages—except Portuguese. What we couldn’t have planned was the impact of the Orca element. On the rescue service dock at Peniche, reporters and a television camera arrived, and

“Orca Attacks Yacht” was their angle, though Severin told the press repeatedly that the “attack” seemed more like playful behavior to him. The local authorities, however, took the Orca incident far more seriously and, if possible, planned to keep us there until the news flurry subsided.

Carlos Pinto, owner/manager of the Peniche Marina, gently explained that because of the press coverage, the local authorities, the police, the port management, the state rescue organization, all had to make doubly sure that any repair made met their standard. They wanted a haul-out. They wanted an official inspection. As Pinto hinted, they wanted to be free of any responsibility. If these crazy foreigners came to grief again in Portugal, they might be blamed.

But by luck, the large fishing boatyard had a 300-ton crane, not equipment small enough to handle the little yacht, and the yacht club simply did not want to be involved. We decided on a “dry out” using the 10-foot tides to perch the boat, securely tied up to a large stone pier, until low tide exposed the rudder for inspection.

There were no tooth marks or broken pieces at the bottom of the rudder, just round marks where the Orcas had slammed into it with their heads

Meanwhile a kind of Orca focus spread. On a nearby slip, a Moody 32 had also been hit by Orcas on the way down the Portuguese coast, and the English owner, Steve Clemens, told me that the rudder hit was so hard that the self-steering arm that moves the boat’s tiller had been ripped out of its bolts in the cockpit.

“If someone had been there, it would have broken his arm,” Clemens said. A portion of the bottom of his blade and skeg rudder had been bitten off.

A young Swede, Michael, captaining his first season with six guests on a stout 52-foot cutter, said he’d researched and found that boats were using strange methods to scare Orcas off. Some (including sardine trawlers) were dragging bags of rags soaked in diesel fuel, hoping that the Orcas would not like to swim through the oil sheen as they “blew” for breath. Others advised making loud noises, perhaps by pounding on metal tubes dragged from the cockpit rail. Another method was to trail a large bumper, on the theory that the whales simply wanted something to play with. Michael said he would sail only in the daytime and remain closer to the coast than the 20-meter line, as the whales prefer deep water.

The only impact for us was to spend a wearisome afternoon trudging through industrial Peniche hardware stores and salvage yards looking for a suitable tube to fashion a noisemaker. Explaining this mission created language difficulties you cannot believe.

With the boat dried out, we hired Ben Ponroy, a respected mechanic. We had taken the rudder post apart, and the trouble became plain. The round stainless rudder stock was attached at the bottom of the keel. At the top, in the cockpit, the tiller was attached to the stock by a circular fitting, clamped with strong bolts, and locked to the round stock by a bolt through a cut-away, which should have prevented any movement at all. This bolt was seriously worn by 30-plus years of use and bent by the shock of the whale’s blow. It was easy for Ponroy to repair it. The rudder itself was undamaged, though the impact points of the whales were clear on the anti-fouling paint.

Of Orcas and yachts

In press reports of Orca attacks on yachts, two distinct schools emerged. One took the tack that the Orcas, like other predators, should be kept in check, perhaps by killing them. But the other school claimed that the Orcas were simply adapting to present conditions, and with dog-like intelligence, had found a way to strip tuna and other species from the illegal and almost invisible drift nets now being used. Like hawks and vultures that had a habitat beside US superhighways, the Orcas seemed to see that human equipment or boat keels in the sea might mean a meal.

Some authorities quoted in the press say it was overfishing and water warming—climate change—that brought the Orcas to southern Portugal coasts and to Gibraltar, where Orca “incidents” were more frequent. These authorities said the attacks on yachts were simply signs of desperation by a species under pressure. The irony was that for once, man, the greatest predator of the seas, had found a whale tough enough to adapt and fight back.

No expert in our brief research would say Orcas wouldn’t appear on the Eastern Seaboard.

Though it took three days, Ben the mechanic’s solution convinced authorities we should be allowed to go; we were thoroughly fed up with Portuguese bureaucrats and prohibitions. I’d taken to scrubbing the bottom with the deck brush of Barbarella, just to have something to do, finding it hot and disagreeable work in the sandy muck.

Carlos Pinto and a couple of uniformed Port police were standing by when Pinto held up his hand: “You are not allowed to scrub the bottom here,” he said in English, while the other men grinned.

It was enough. I threw down my broom and yelled at them: “Portugal!”

Pinto rushed over, put a hand on my shoulder. “It was only a joke,” he said, “a very bad one.”

A day and a half later, Lisbon.

~by Duncan Spencer